The title of the musical, Castle Gillian, implies that the house in which the Morris clan reside is a castle of some description. In fact, the Morris’s live in a somewhat run-down Georgian country house which has become increasingly dilapidated with the failing fortunes of the once mighty racing stable.

So why in the story is it referred to a castle? Our view is that it is so-named as a metaphor for a ‘place to be defended’ which is completely in keeping with the drama of our story.

So, what is an Irish castle as opposed to the better know Saxon and Norman castles we associate with England and Scotland?

THE EARLIER CASTLES

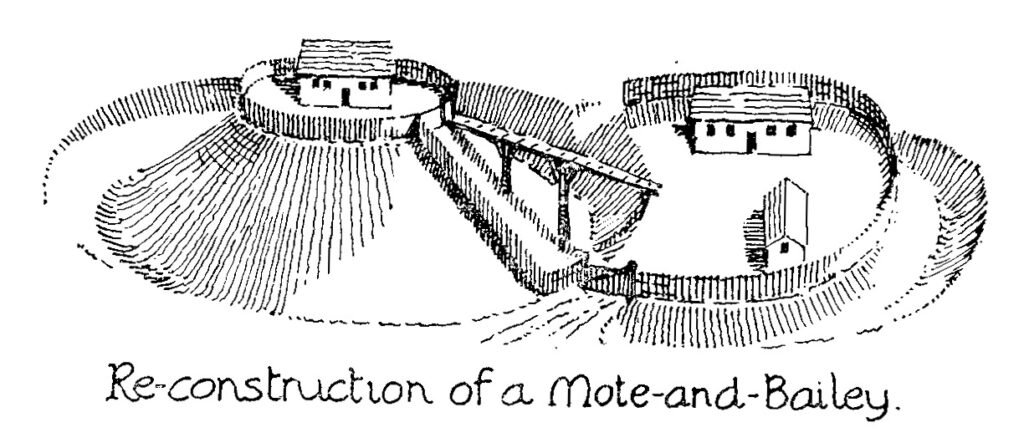

Apart from the well-known medieval fortress of mortared stone, in Ireland the term ‘castle’ can be applied to fortresses of earth: mounds or mote-and-bailey erections thrown up by the Normans. Not only are these fortresses of earth – deeply fossed and crowned by palisades and towers of timber the progenitors of the later stone erections – but also well-defended tower-houses characteristic of the 15th and 16th centuries.

And so, too, the native Irish dún, cashel, great ring fort or rath are equally worthy of the title. Regrettably, there remains no vestige of a native Irish castle of the 12th century to be seen today in Ireland.

The mote-and-bailey castles most probably belong to the years between the coming of Strongbow and his followers, and the close of the 12th century.

The great castle building period in Ireland extended from the end of the 12th century for about 120 years. Throughout the 14th and the first half of the 15th century, we hear of no castle building. The reason? The invasion by Edward Bruce brought disorder and famine in its train while the great plague, the black death of 1349, reduced Ireland to even greater levels of poverty.

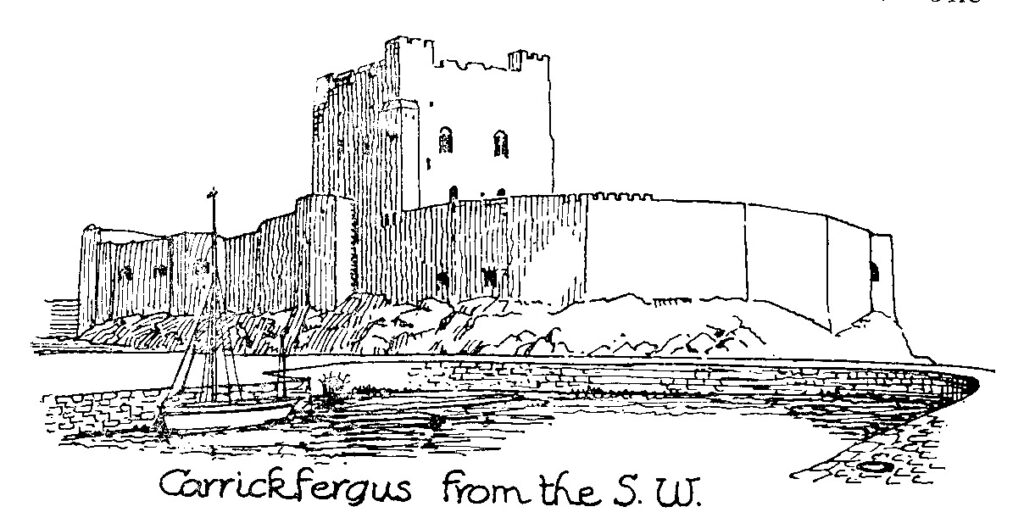

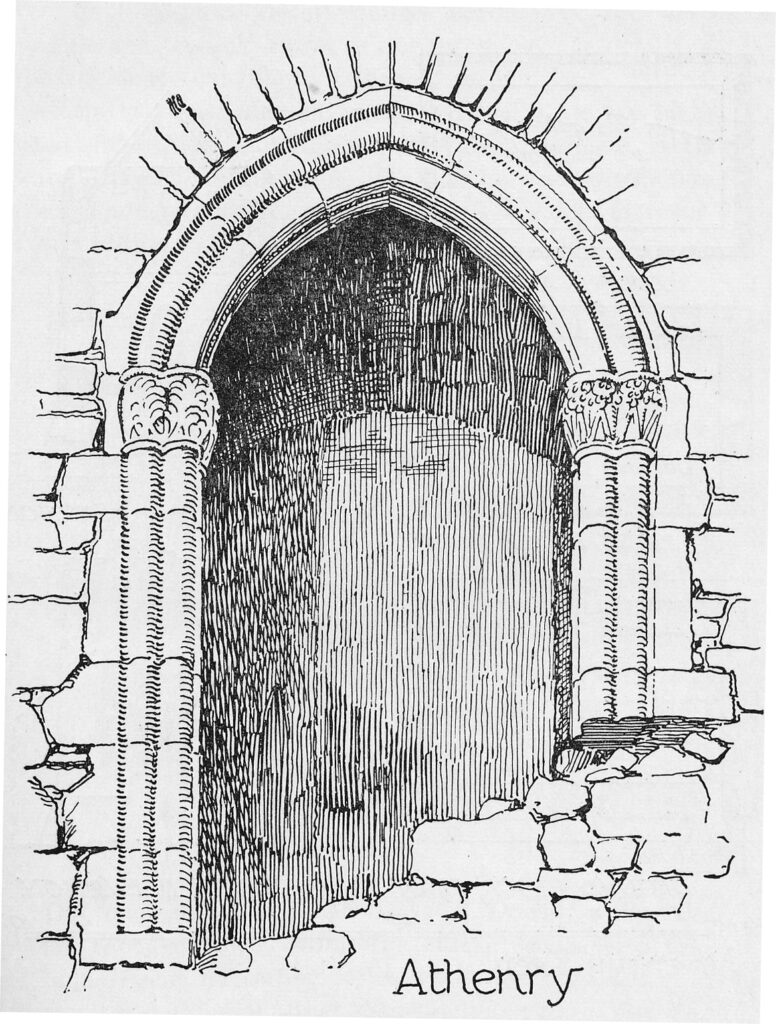

Most of the stone erected castles up to about the middle of the 13th century have as their dominating feature a great tower, a ‘donjon’ commonly called a keep. While in some castle the keep forms part of the outer defences, in others it is isolated within the curtain walls. Examples of the former include Carrickfergus, Rinnduin and Greencastle (Donegal). The castles of Trim, Adare, Maynooth, Athenry and Greencastle (Down) to the latter.

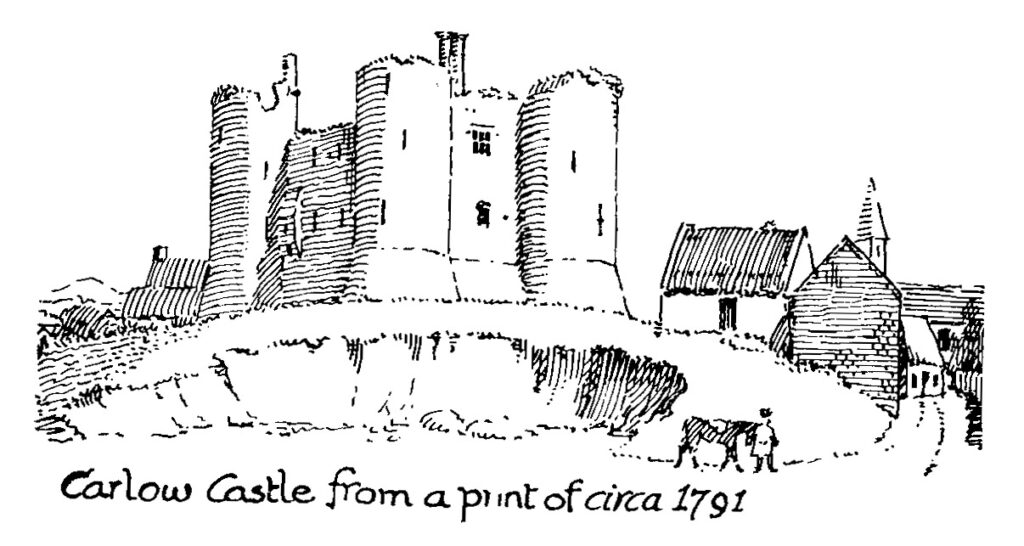

In a third group are the castles with towered keeps, a speciality Irish type. To this group belong Carlow, Ferns, Lea and Terryglass and the now vanished castle of Wexford, as well as the reconstructed castle at Enniscorthy.

The round keep, ‘donjon’ or ‘Juliet’ is rather less common in Ireland than in England or France. The fashion did not persist suggesting earlier dates of these castles around the first decade of the 13th century.

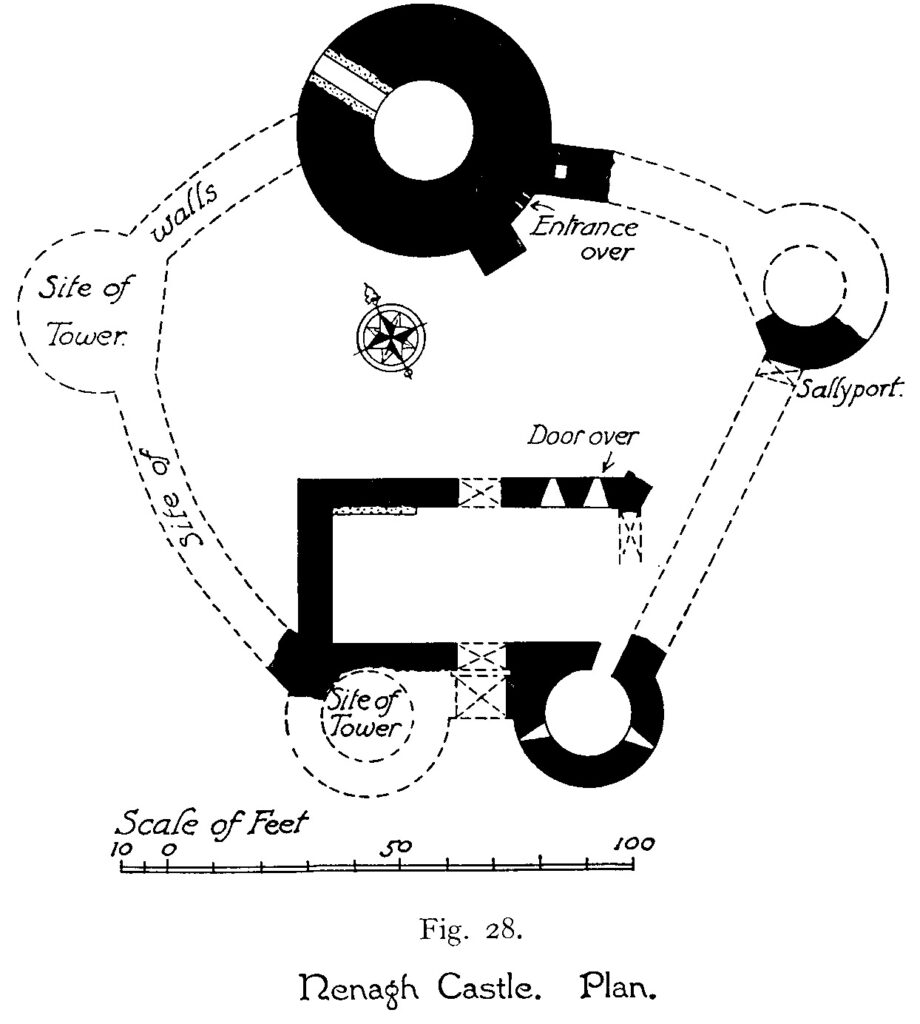

NENAGH castle, in Co. Tipperary, has the finest cylindrical keep in Ireland. The keep formed part of the perimeter of the fortress being incorporated in the curtains surrounding a small, five-sided, courtyard.

THE TOWERED OR TURRETED KEEPS

The keeps of this form seem to be perculiar to Ireland in the first half of the 13th century. Those that remain in Ireland are greatly ruined, but their plans are sometimes discernible from the remaining fragments.

The finest of the towered keeps is at FERNS (Co. Wexford). At LEA, in Leix, near Portarlington is another fine example. Here the outer wall extends to the bank of the river Barrow nearby. Lea was a stronghold of the Fitzgeralds.

THE TOWER HOUSES

From about 1440 onwards there was a great building revival epitomized by the addition of belfry towers and cloister arcades to the monasteries and the erection of completely new houses for the Friars – both Franciscan and Domenican – particularly in the west of the country. It is to this period that by far the greater number of the single towers belong.

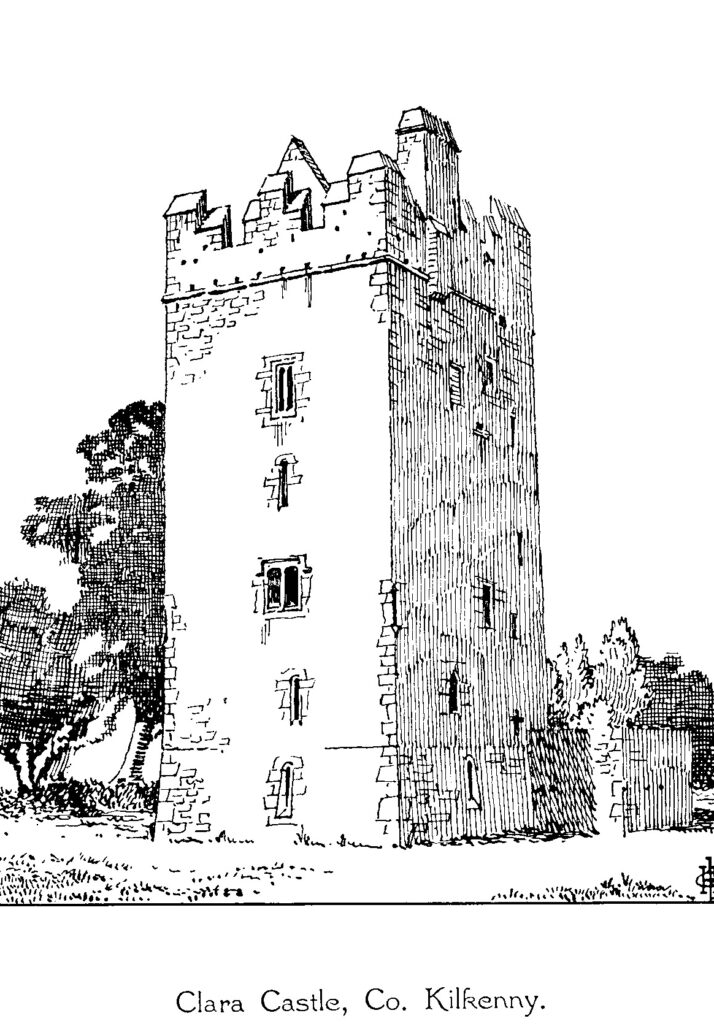

The nearly perfect example of the single tower is the castle at CLARA (Co. Kilkenny). The structure and its features have many points of interest. Like most other Irish buildings of the period it is built of limestone.

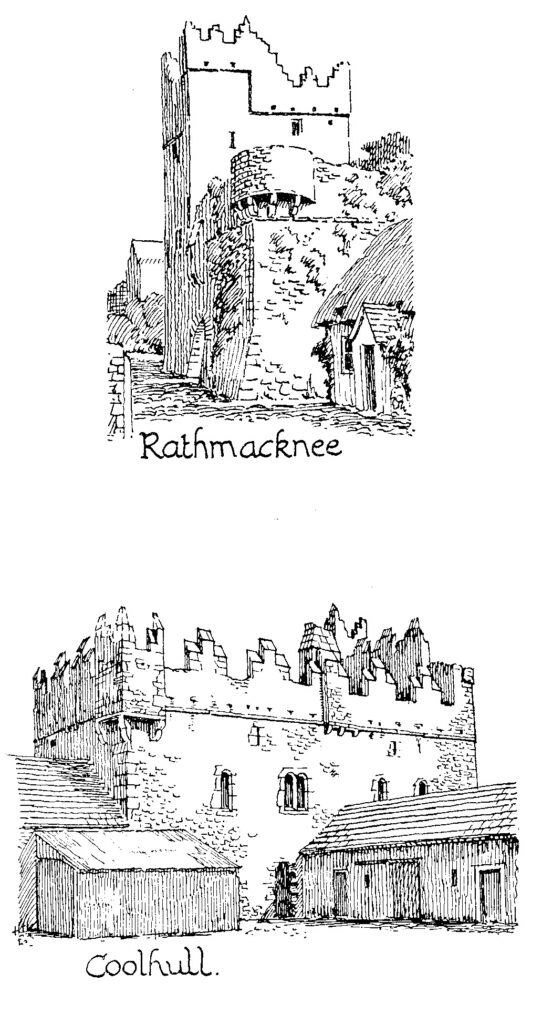

Likewise, Rathmacknee castle (Co. Wexford) is very complete and most picturesque small castle built of warm-coloured stone.

Also in Co. Wexford is the very attractive COOLHULL, a late 16th century castle which is not a tower but a longish oblong of only two stories in height rising in a small narrow tower at one end.

The Clara type castle persisted well into the 17th century as is evidenced by the very well-preserved castle of DERRYHIVENNY (Co. Galway).

THE LARGER CASTLES

Perhaps today the most widely known is the castle of BLARNEY (Co. Cork). It’s tower, some 85 feet in height, is surely the most frequently photographed Irish building.

There are several other great towers, somewhat less massive than that of Blarney, but each possessing special points of interest.

Perhaps the finest is that of BUNRATTY (Co. Clare). A 15th century erection, it is an oblong erection, lofty, and furnished at each corner with a square tower or turret.

Bunratty has a stirring history of ownership, changing hands depending on fealty to English Kings or feuds between Irish clans. It has been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries.

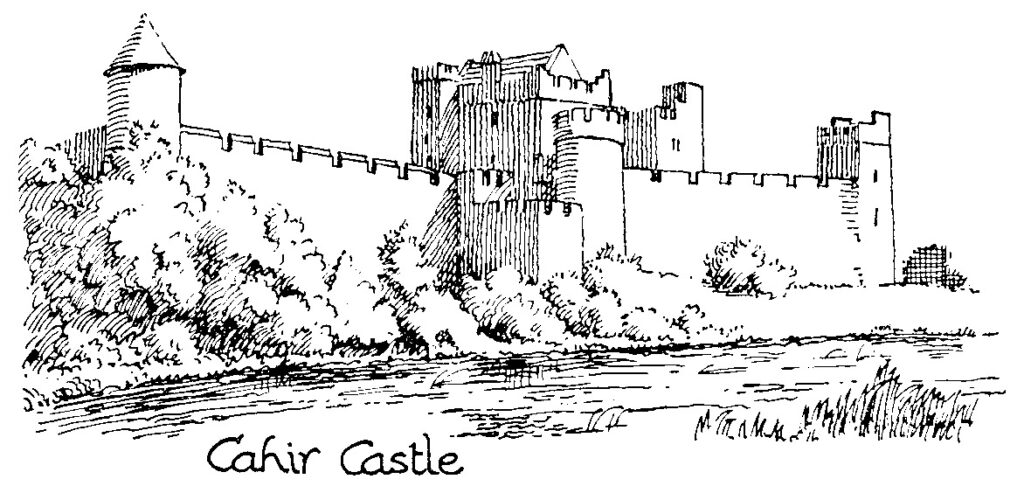

The largest, mainly 15th century, castle in Ireland is the splendid CAHIR (Co. Tipperary). The site at Cahir was occupied by earlier fortresses many centuries before the castle was built. A fort there was destroyed in the 3rd Century and, in later times, it was one of the residences of Brian of the Tributes. The place is also mentioned in the Brehon Laws.

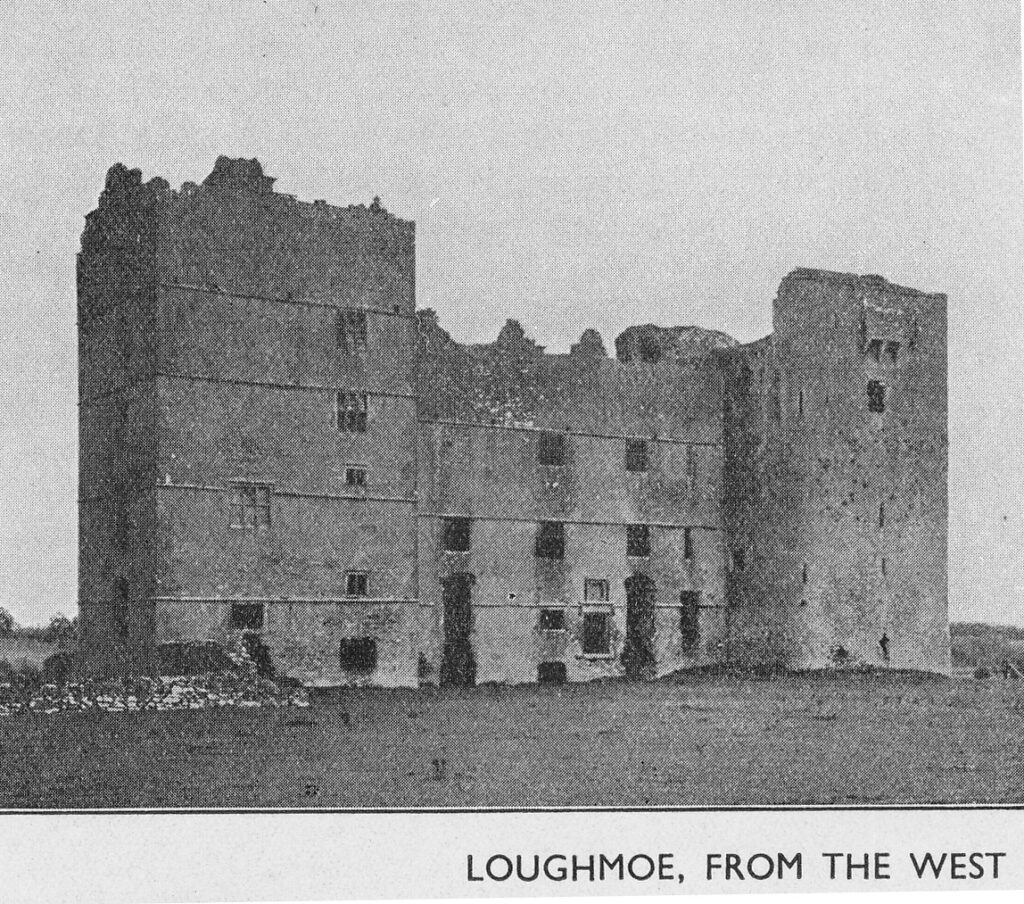

The castle of the Purcells at LOUGHMOE, near Templemore (Co. Tipperary) is a 15th century rectangular tower to which is attached a long and much larger house nearly two hundred years younger.

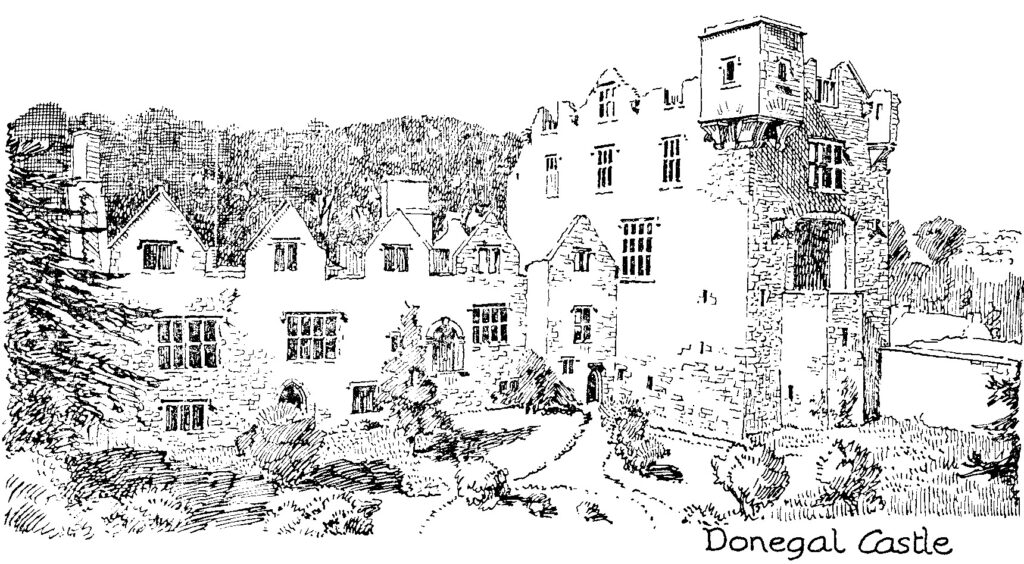

The fine Jacobean wing at DONEGAL castle, which has so much of the authentic flavour of an English manor house, is a good example of the transformation of a fortress into a comfortable residence. It is attached to a massive tower built in the 16th century and is said to have been burned by the the famous Hugh Roe before his final departure from Ireland after the battle of Kinsale.