Returning to this subject now. I don’t think it is unreasonable to to compare the music of México to its many baroque cathedrals and churches. Plans and elevations were Spanish in design, but the construction itself was the work of natives and they left their stamp on every element of the buildings. So with folk and popular music, the framework is mainly Spanish in tonality and mode, and in the structure of its melody, harmony and meter; but the melodic inflection and ornamentation, and rhythmic combinations show definite Indian influence.

Getting to understand the primitive folk music, and especially the oldest surviving tribal music and dances of México is important to me for this project but, alas, not easy to attain. The Library of Congress did release an album under sponsorship of the old Inter-American Indian Institute by Henrietta Yurchenko and the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature did begin a systematic collection of the many types of songs and dances, but currently I can’t find out any further information about their collections. Regrettable, but nonetheless here are some insights gleaned so far from other sources:

Let’s begin with the Corrido. Historically, this song form is a narrative folk-popular ballad telling of the exploits of national or local heroes, the latest crime, flood, or any other outstanding event. Whereas the melodic phrase is repeated for each stanza, instrumental interludes of equal or varying length are common.

The Huapango, conversely, is a dance with fast and complicated steps for two people, or groups of pairs. The cross-rhythms are important: one instrument plays in 2/4 meter, another in 3/4 meter, and a third in 6/8 meter – a pretty dazzling combination really!

[Sidebar] This is all very well, but typesetting music using commonly employed computer music programs, incorporating multi-time signature music, is not a happy place to find oneself! It’s completely possible, but time-consuming and laborious in the extreme.

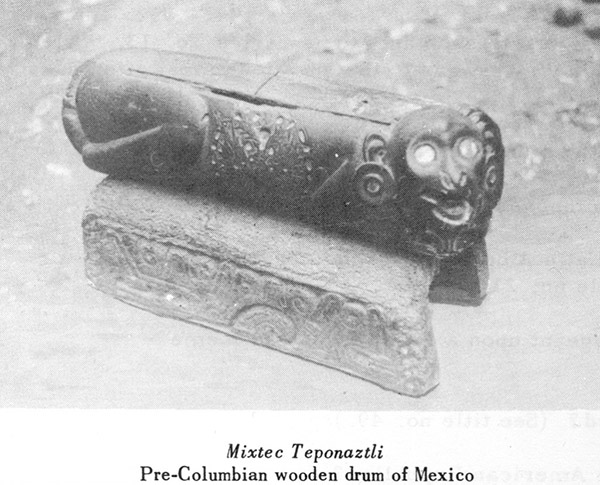

As pointed out in the previous post on this subject, composers like Manuel M. Ponce (1882-1948) and Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) both made concerted efforts to incorporate native folk-song elements; including in the case of Chávez, the use of ancient instruments in the score of Xochipili-Macuilxochitl as an evocation of the sound of a pre-Columbian orchestra.

Méxican composers such as Silvestre Revueltas (1899-1940) whose untimely death was one of the great losses to music in the 20th-Century, wrote music in sharp contrast to the rigorous and stylized of Chavéz. Reveueltas’s best-known music are the symphonic essays: Cuauhnáhuac, Colorines, Janitzio, and Ventanas, Camino y Esquinas. Add to this his String Quart No. 2, Magueyes (how many of you know this?); the score for the film, Redes (an unknown gem); Homage to García Lorca; and the Seven Songs for voice and piano.

Later still, composers such as Luis Sandi, Miguel Bernal Jiménez (he wrote the opera Tata Vasco), Salvador Contreras, Eduardo H. Moncada, J. Pablo Moncayo and Blas Galindo all studied under the tutelage and encouragement of Chávez.

One of the most-loved composers of popular Mexican music is Augustín Lara.